Saadia Gaon

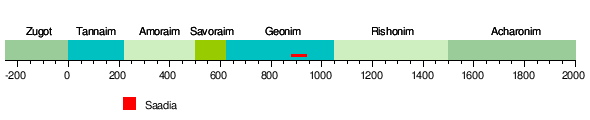

Saʻadiah ben Yosef Gaon (b. Egypt 882/892, d. Baghdad 942,[1][2] Arabic: سعيد بن يوسف الفيومي Saʻīd bin Yūsuf al-Fayyūmi, Hebrew: סעדיה בן יוסף גאון, Sa'id ibn Yusuf al-Dilasi, Saadia ben Yosef aluf, Sa'id ben Yusuf ra's al-Kull[3]) was a prominent rabbi, Jewish philosopher, and exegete of the Geonic period.

The first important rabbinic figure to write extensively in Arabic, he is considered the founder of Judeo-Arabic literature.[4] Known for his works on Hebrew linguistics, Halakha, and Jewish philosophy, he was one of the more sophisticated practitioners of the philosophical school known as the "Jewish Kalam" (Stroumsa 2003). In this capacity, his philosophical work Emunoth ve-Deoth represents the first systematic attempt to integrate Jewish theology with components of Greek philosophy. Saadia was also very active in opposition to Karaism, in defense of rabbinic Judaism.

Contents |

Biography

Early life

Saadia, in "Sefer ha-Galui", stresses his Jewish lineage, claiming to belong to the noble family of Shelah, son of Judah (see Chronicles 1 4:21), and counting among his ancestors Hanina ben Dosa, the famous ascetic of the first century. Expression was given to this claim by Saadia in calling his son Dosa (this son later served as Gaon of Sura from 1013–1017). Regarding Joseph, Saadia's father, a statement of Aaron ben Meir has been preserved saying that he was compelled to leave Egypt and died in Jaffa, probably during Saadia's lengthy residence in the Holy Land. The usual epithet of "Al-Fayyumi" refers to Saadia's native place, the Fayum in upper Egypt; in Hebrew it is often given as "Pitomi," derived from a contemporary identification of Fayum with the Biblical Pithom (an identification found in Saadia's own works).

At a young age he left his home to study under the Torah scholars of Tiberias. At age 20 Saadia completed his first great work, the Hebrew dictionary which he entitled Agron. At 23 he composed a polemic against the followers of Anan ben David, particularly Solomon ben Yeruham, thus beginning the activity which was to prove important in opposition to Karaism, in defense of rabbinic Judaism. In the same year he left Egypt and settled permanently in Palestine.

Dispute with Ben Meir

In 922 a controversy arose concerning the Hebrew calendar, that threatened the entire Jewish community. Since Hillel II (around 359 CE), the calendar had been based on a series of rules (described more fully in Maimonides' Code[5]) rather than on observation of the moon's phases. One of these rules required the date of Rosh Hashanah to be postponed if the calculated lunar conjunction occurred at noon or later. Rabbi Aaron ben Meir, the Gaon of the leading Talmudic academy in Israel (then located in Ramle), claimed a tradition according to which the cutoff point was 642/1080 of an hour (approximately 35 minutes) after noon.[6] In that particular year, this change would result in a two-day schism with the major Jewish communities in Babylonia: according to Ben Meir the first day of Passover would be on a Sunday, while according to the generally accepted rule it would be on Tuesday.

Saadia was in Aleppo, on his way from the East, when he learned of Ben Meir's regulation of the Jewish calendar. Saadia addressed a warning to him, and in Babylon he placed his knowledge and pen at the disposal of the exilarch David ben Zakkai and the scholars of the academy, adding his own letters to those sent by them to the communities of the Diaspora (922). In Babylonia he wrote his "Sefer ha-Mo'adim," or "Book of Festivals," in which he refuted the assertions of Ben Meir regarding the calendar, and helped to avert from the Jewish community the perils of schism.

Appointment as Gaon

His dispute with Ben Meir was an important factor in the call to Sura which he received in 928. The exilarch David ben Zakkai insisted on appointing him as Gaon (head of the academy), despite the weight of precedent (no foreigner had ever served as Gaon before), and against the advice of the aged Nissim Nahrwani, a Resh Kallah at Sura, who feared a confrontation between the two strong-willed personalities, David and Saadia. (Nissim declared, however, that if David was determined to see Saadia in the position, then he would be ready to become the first of Saadia's followers.[7])

Under his leadership, the ancient academy, founded by Rav, entered upon a new period of brilliancy.[8] This renaissance was cut short, though, by a clash between Saadia and David, much as Nissim had predicted.

In a probate case Saadia refused to sign a verdict of the exilarch which he thought unjust, although the Gaon of Pumbedita had subscribed to it. When the son of the exilarch threatened Saadia with violence to secure his compliance, and was roughly handled by Saadia's servant, open war broke out between the exilarch and the gaon. Each excommunicated the other, declaring that he deposed his opponent from office; and David b. Zakkai appointed Joseph b. Jacob as gaon of Sura, while Saadia conferred the exilarchate on David's brother Hassan (Josiah; 930). Hassan was forced to flee, and died in exile in Khorasan; but the strife which divided Babylonian Judaism continued. Saadia was attacked by the exilarch and by his chief adherent, the young but learned Aaron ibn Sargado (later Gaon of Pumbedita, 943-960), in Hebrew pamphlets, fragments of which show a hatred on the part of the exilarch and his partisans that did not shrink from scandal. Saadia did not fail to reply.

Later years

He wrote both in Hebrew and in Arabic a work, now known only from a few fragments, entitled "Sefer ha-Galui" (Arabic title, "Kitab al-Ṭarid"), in which he emphasized with great but justifiable pride the services which he had rendered, especially in his opposition to heresy.

The seven years which Saadia spent in Baghdad did not interrupt his literary activity. His principal philosophical work was completed in 933; and four years later, through Ibn Sargado's father-in-law, Bishr ben Aaron, the two enemies were reconciled. Saadia was reinstated in his office; but he held it for only five more years. David b. Zakkai died before him (c. 940), being followed a few months later by the exilarch's son Judah, while David's young grandson was nobly protected by Saadia as by a father. According to a statement made by Abraham ibn Daud and doubtless derived from Saadia's son Dosa, Saadia himself died in Babylonia at Sura in 942, at the age of sixty, of "black gall" (melancholia), repeated illnesses having undermined his health.

Works

Exegesis

Saadia translated most, if not all, of the Bible into Arabic, adding an Arabic commentary, although there is no citation from the books of Chronicles.

Hebrew Linguistics

- Agron

- Kutub al-Lughah

- "Tafsir al-Sab'ina Lafẓah," a list of seventy (properly ninety) Hebrew (and Aramaic) words which occur in the Hebrew Bible only once or very rarely, and which may be explained from traditional literature, especially from the Neo-Hebraisms of the Mishnah. This small work has been frequently reprinted.

Halakhic Writings

- Short monographs in which problems of Jewish law are systematically presented. Of these Arabic treatises of Saadia's little but the titles and extracts is known, and it is only in the "Kitab al-Mawarith" that fragments of any length have survived.

- A commentary on the thirteen rules of Rabbi Ishmael, preserved only in a Hebrew translation. An Arabic methodology of the Talmud is also mentioned, by Azulai, as a work of Saadia under the title "Kelale ha-Talmud".

- Responsa. With few exceptions these exist only in Hebrew, some of them having been probably written in that language.

- The "Siddur": see Siddur of Saadia Gaon. Of this synagogal poetry the most noteworthy portions are the "Azharot" on the 613 commandments, which give the author's name as "Sa'id b. Joseph", followed by the title "Alluf," thus showing that the poems were written before he became gaon.

Philosophy of Religion

- Emunoth ve-Deoth (Kitab al-Amanat wal-l'tikadat): This work is considered to be the first systematic attempt to synthesize the Jewish tradition with philosophical teachings. Prior to Saadia, the only other Jew to attempt any such fusion was Philo (1989 Ivry).

- "Tafsir Kitab al-Mabadi," an Arabic translation of and commentary on the Sefer Yetzirah, written while its author was still residing in Egypt (or Israel).

Polemical writings

- Refutations of Karaite authors, always designated by the name "Kitab al-Radd," or "Book of Refutation." These three works are known only from scanty references to them in other works; that the third was written after 933 is proved by one of the citations.

- "Kitab al-Tamyiz" (in Hebrew, "Sefer ha-Hakkarah"), or "Book of Distinction," composed in 926, and Saadia's most extensive polemical work. It was still cited in the twelfth century; and a number of passages from it are given in a Biblical commentary of Japheth ha-Levi.

- There was perhaps a special polemic of Saadia against Ben Zuta, though the data regarding this controversy between is known only from the gaon's gloss on the Torah.

- A refutation directed against the rationalistic Biblical critic Hiwi al-Balkhi, whose views were rejected by the Karaites themselves;

- "Kitab al-Shara'i'," or "Book of the Commandments of Religion."

- "Kitab al-'Ibbur," or "Book of the Calendar," likewise apparently containing polemics against Karaite Jews;

- "Sefer ha-Mo'adim," or "Book of Festivals," the Hebrew polemic against Ben Meir which has been mentioned above.

- "Sefer ha-Galui," also in Hebrew and in the same Biblical style as the "Sefer ha-Mo'adim," being an apologetic work directed against David b. Zakkai and his followers.

Significance

Saadia Gaon was a pioneer in the fields in which he toiled. The foremost object of his work was the Bible; his importance is due primarily to his establishment of a new school of Biblical exegesis characterized by a rational investigation of the contents of the Bible and a scientific knowledge of the language of the holy text.

Saadia's Arabic translation of the Bible is of importance for the history of civilization; itself a product of the Arabization of a large portion of Judaism, it served for centuries as a potent factor in the impregnation of the Jewish spirit with Arabic culture, so that, in this respect, it may take its place beside the Greek Bible-translation of antiquity and the German translation of the Pentateuch by Moses Mendelssohn. As a means of popular religious enlightenment, Saadia's translation presented the Scriptures even to the unlearned in a rational form which aimed at the greatest possible degree of clearness and consistency.

His system of hermeneutics was not limited to the exegesis of individual passages, but treated also each book of the Bible as a whole, and showed the connection of its various portions with one another.

The commentary contained, as is stated in the author's own introduction to his translation of the Pentateuch, not only an exact interpretation of the text, but also a refutation of the cavils which the heretics raised against it. Further, it set forth the bases of the commandments of reason and the characterization of the commandments of revelation; in the case of the former the author appealed to philosophical speculation; of the latter, naturally, to tradition.

The position assigned to Saadia in the oldest list of Hebrew grammarians, which is contained in the introduction to Ibn Ezra's "Moznayim," has not been challenged even by the latest historical investigations. Here, too, he was the first; his grammatical work, now lost, gave an inspiration to further studies, which attained their most brilliant and lasting results in Spain, and he created in part the categories and rules along whose lines was developed the grammatical study of the Hebrew language. His dictionary, primitive and merely practical as it was, became the foundation of Hebrew lexicography; and the name "Agron" (literally, "collection"), which he chose and doubtless created, was long used as a designation for Hebrew lexicons, especially by the Karaites. The very categories of rhetoric, as they were found among the Arabs, were first applied by Saadia to the style of the Bible. He was likewise one of the founders of comparative philology, not only through his brief "Book of Seventy Words," already mentioned, but especially through his explanation of the Hebrew vocabulary by the Arabic, particularly in the case of the favorite translation of Biblical words by Arabic terms having the same sound.

Saadia's works were the inspiration and basis for later Jewish writers, such as Berachyah in his encyclopedic philosophical work Sefer Hahibbur (The Book of Compilation).

Relations to Mysticism

In his commentary on the "Sefer Yetzirah", Saadia sought to render lucid and intelligible the content of this esoteric work by the light of philosophy and scientific knowledge, especially by a system of Hebrew phonology which he himself had founded. He did not permit himself in this commentary to be influenced by the theological speculations of the Kalam, which are so important in his main works. In introducing "Sefer Yetzirah"'s theory of creation he makes a distinction between the Biblical account of creation ex nihilo, in which no process of creation is described, and the process described in "Sefer Yetzirah" (matter formed by speech). The cosmogony of "Sefer Yetzirah" is even omitted from the discussion of creation in his magnum opus "Kitab al-Amanat wal-I'tiḳadat." From this it may be concluded that he regarded the "Sefer Yetzirah" as presenting one among many competing theories of creation, and not as authoritative. Concerning the supposed attribution of the book to the patriarch Abraham, he allows that the ideas it contains might be ancient, but that grammatical analysis shows that the text could not predate the Bible. Nonetheless, he clearly considered the work worthy of deep study and echoes of "Sefer Yetzirah"'s cosmogony do appear in "Kitab al-Amanat wal-I'tiḳadat" when Saadia discusses his theory of prophecy.

Notes

- ↑ The traditional birth year of 892 was exclusively cited before 1921 and is still occasionally cited. It rests on a statement by the twelfth-century historian Abraham ibn Daud that Saadia was "about fifty" years old when he died. The modern birth year of 882 rests on an 1113 CE Genizah fragment containing a list of Saadia's writings compiled by his sons eleven years after his death, which stated that he was "sixty years less forty … days" at death. Henry Malter, "Postscript", Saadia Gaon: His life and works (1921) 421–428. Jacob [Jocob] Mann, "A fihrist of Sa'adya's works", The Jewish Quarterly Review new series 11 (1921) 423-428. Malter rejected 882 because it was in conflict with other known events in Saadia's life. He suspected an error by a copyist. 882 is now generally accepted because its source is closer in both time and space to his death.

- ↑ Bar Ilan CD-ROM

- ↑ Gil, Moshe & Strassler, David (2004). Jews in Islamic countries in the Middle Ages. Leiden: Brill. p. 348. ISBN 900413882X.

- ↑ Scheindlin, Raymond P. (2000). A Short History of the Jewish People: From Legendary Times to Modern Statehood (Illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press US. p. 80.. ISBN 0195139410, 9780195139419. http://books.google.com/?id=bfsuicMmrE0C&pg=PA80&dq=saadia+arabic+jewish#v=onepage&q=saadia%20arabic%20jewish.

- ↑ Laws of the Sanctification of the Moon, chs. 6-10, written c. 1170.

- ↑ Various suggestions have been made as to where Ben Meir got this figure. A contemporary author, Remy Landau, suggests that he wanted to optimize the rule and thereby reduce the frequency of this postponement (The Meir-Saadia Calendar Controversy).

- ↑ Yuchasin, section 3, account by Nathan the Babylonian.

- ↑ Letter of Sherira Gaon.

See also

- Emunoth ve-Deoth

- Jewish philosophy

- Judaism

- Rabbi

References

- This article incorporates text from the 1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

- Salo W. Baron, "Saadia's communal activities", Saadia Anniversary Volume (1943) 9-74.

- M. Friedlander, "Life and works of Saadia", The Jewish Quarterly Review 5 (1893) 177-199.

- Ivry, Alfred L. (1989). "The contribution of Alexander Altmann to the study of medieval Jewish philosophy". In Arnold Paucker. Leo Baeck Institute Year Book XXXIV. London: Secker & Warburg. pp. 433–440.

- Henry Malter, Saadia Gaon: His life and works (Morris Loeb Series, Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1921, several later reprints).

- Stroumsa, Sarah (2003). "Saadya and Jewish kalam". In Frank, Daniel H.; Leaman, Oliver. The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Jewish Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–90. ISBN 978-0521652070

- Wein, Berel (November 1993). Herald of Destiny: The Story of the Jews 750-1650. Brooklyn, NY: Shaar Press. pp. 4–12. ISBN 0-89906-237-7.

External links

- Resources > Medieval Jewish History > Geonica The Jewish History Resource Center - Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry